“Eddie is someone I have in mind for music every day. I didn’t even talk to him about it until I was back and done with the movie. He was not familiar with the book. But two days later he was reading it, and he called me up and said, ‘I got to do this.'”

– Sean Penn

The final element that weaves through the entire film is the music, which was on Penn’s mind from the very beginning, with many cues and specific songs written directly into the script. Ultimately, the score would combine original songs and music from Eddie Vedder along with the guitar compositions of Michael Brook and Kaki King.

“More and more as we were shooting I started to hear the voice of Eddie Vedder as the soul of Chris McCandless” says Penn. “Meanwhile, as Jay Cassidy and I were putting together assemblies each night to music, I found myself over and over going to the well of Michael Brook’s music and that began to feel sonically like the right approach. Then, Kaki King was recommended by Martin Hernandez, our sound designer, and I listened to some of her stuff and she came on board. And then, after all that, I asked Eddie if he would read the book and he did and he jumped right in writing songs, but he also went beyond that, writing instrumental pieces as well. Finally, we did some recording sessions up in Seattle with Michael and Eddie and Charlie Musslewhite and, between all of them, they just knocked it out of the park.”

Vedder who became friends with Penn years ago while writing music for Dead Man Walking, recalls Penn calling him up and asking him to come see the just-completed movie. “I thought it was great and there didn’t seem to be anything missing. It already had lots of good music,” he says. “But Sean said ‘just go with it and see what happens.’ So we spent three days in the studio and I sent him about a half hour’s worth of music. Then, he said, ‘if I could get some more of this stuff you could become the interior voice of the character.’ He saw the music as becoming almost what’s inside the kid’s head.”

He didn’t hesitate to dive in at Sean’s urging, knowing it would take him to unexpected places. “Sean is an incredibly special person,” Vedder remarks, “and let’s say you’re standing on the edge of a pool wondering if you should jump in, Sean’s the perfect person to push you.”

Having never read the book, Vedder remedied that and found ample inspiration in Chris McCandless. “It wasn’t hard for me to understand this kid,” he admits. “I still feel so connected and have such strong memories of being at that age where you see the bullshit in the world and want to know how to address it, how can you maintain some idealism, and how to not become the same authority fiqures that you’re growing up around. This was an opportunity to kind of revisit that stuff. I think it takes real guts to do what Chris did and even if there was recklessness involved, it’s the kind of reckless we miss later when we’re settled in and wonder what we could have done with our lives.”

Vedder explains that while he was writing his own younger brother, also named Chris, went off to South Africa to meditate, and momentarily lost contact with the family. “No one had heard from him for about 2 months and suddenly I felt like Carine,” he says. “There were things happening in real life that were really parallel to the story.”

The songs themselves emerged in a rough, spontaneous style, meshing with the road-trip spirit of the film. Vedder likens the sound to demos Pete Townsend of The Who recorded, playing all the instruments himself. “It was a different character than a band playing it – it’s simpler, but it’s also purer,” he says. He notes that he found himself constantly swapping instruments as he composed. :There’s a mandolin piece,” he points out, “and I think this was only the second time I’ve played the mandolin, but it really just fit the emotion.”

Used to a more open-ended writing style, Vedder also found himself enjoying the relative constrictions of writing songs to scenes. “This was really different for me because it’s so streamlined,” he noted. “You had a lot of parameters to work with- you know, this song has to be two minutes long and it’s at this point in his journey and there has to be instrumental music half-way through because the voice-over comes in. But, ultimately, it really came down to serving Sean and serving Chris McCandless, whom I felt a real responsibility to as well.”

Things came together so perfectly for Vedder, he began to wonder at the source of it. “There was something in the air, you couldn’t deny something was going on,” he says. “The writing was so easy and the music came together in strange ways where beats would land on a shutting car door or the pump organ would mesh with the way Emile’s shoulders were going up and down. It was almost as if someone was helping from a non-tangible dimension. There was some really strange and quite beautiful elements that helped us along.”

The music- raw, intimate and emotional- further underscores the rich legacy of hard questions and intriguing propositions Chris McCandless left behind when he passed from this world. This is also a reflected in a line that Penn wrote at the end of his screenplay for Into The Wild. It reads: “Chris died alive.” When asked to elucidate on this, Penn sums it all up concisely: “Having lived, he still lives in us.”

The Pearl Jam frontman talks about what inspired him while crafting solo songs for the ”Into the Wild” and ”Body of War” soundtrack

Entertainment Weekly | Sepember 13, 2007

By Whitney Pastorek

After 17 years fronting Pearl Jam, Eddie Vedder is stepping out on his own this fall, writing and recording solo tracks for two movie soundtracks. The first, Into the Wild, is Sean Penn’s adaptation of the Jon Krakauer book — the expansive, true story of the life and death of 24-year-old Chris McCandless (played by Emile Hirsch). The second film is Body of War, a documentary co-directed by Ellen Spiro and Phil Donahue that takes a bracing look at the Iraq War through the prism of Tomas Young, a 25-year-old veteran of the conflict who was paralyzed after serving just five days. Given this sudden burst of movie madness, we grabbed a couple minutes to chat with Vedder during an NYC pit stop on his way to Body’s Sept. 11 Toronto Film Festival premiere. Always thoughtful — and slightly sleepy, thanks to an all-nighter he’d just pulled with Penn — here’s what the socially conscious Seattleite had on his mind.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: I heard you guys stayed up until 5:30.

That’s a rumor. [Laughs] No, Sean likes to stay up late. So I’ve got a comrade. Good things get talked about at 5 in the morning. You don’t remember them, but it’s fun while it happens.

Is your friendship with Sean at the heart of your Into the Wild participation?

Yeah, I might have thought about it differently if it was someone else. With this, there was no thought whatsoever. We’d just finished touring with Pearl Jam, and Sean called my second day off or something. So I read the book, and right away it was like, This is not gonna be a stretch. Sean very casually showed up at the house a couple days later — at my door, as if he lived down the street and just walked down — and we watched it together. It was beautiful, and I wept, and it was tremendous. I didn’t know what he needed me for, cause it was great. I remember watching it the first time — it was just me and Sean sitting on the floor watching, you know, with a pack of smokes — and I just wanted to say, like, How’d you get that shot? Wait, did that really happen? Were those wild horses? That grizzly bear, how’d you do that? So it was really difficult to not say a word. The whole thing to me was incredibly moving. And getting into [McCandless’] head, it’s very blatant that this is the last kid that would ever want a movie made about him, and how dangerous that would be to who he was and how he led his life, to be commercialized or trivialized. Thank God it was Sean who did this.

You hadn’t read the book previously?

No. Everyone else I knew had.

It’s one of those books you read in college and decide you’re going to throw away your whole stupid life and run off to the woods and die.

Yeah — or live. Learn from his few mistakes. We were talking about it a bit last night. I think it will not only affect people who did that stuff, who relate to that because they did something similar, but it’ll affect people who didn’t do it, and are wondering why they didn’t, having lost that chance.

One does get older and realize you’re way too immersed in your life to chuck it all and go hike the Appalachian Trail or whatever.

It’s amazing how quickly you can break out, though. You can. It’s right there at all times. The edge is closer than we think. You can put yourself out there in a few hours. And you can always come back, most of the time. Sean and I did about 100 miles through the Grand Canyon a few weeks ago, in kayaks, and came out at Lake Mead. We had a river guide, this great person called Brian Dierker, who plays Rainey in the movie. He doesn’t do commercial trips, he just takes geologists and scientists through there — Sean cast him after they scouted places to shoot. And Sean really took responsibility in the scouting, to the point where if there’s a scene in a tent in the desert, that tent is put exactly where Chris put it. They used photos and lined things up with the mountains, lined it up with the shoreline. And without disturbing the land, they would shoot. They didn’t have to do that. They could have used a backlot or something. You realize it’s not just that Sean made this great movie with these great people, but they had a f—ing hell of a time doing it. It was an adventure, just making it. So the kid had an adventure, and then Sean and the crew and Emile had an adventure.

And you’ve written the soundtrack for the adventure. Did you set out to essentially score the film?

Sean just said, ”Whatever you wanna do. Maybe it’s music, maybe it’s a song.” So I spent three days giving him colors that I could paint with. Different sounds. It would be pump organ and vocal, or it would be an uptempo song. I just gave him 25 minutes of music, stuff I felt that were colors on the palette. And I really didn’t think anything was gonna come out of it. Maybe a little piece or something. As much as I wanted to serve Sean and the project, I just had really low expectations. But instead of saying, ”Okay, cool, I might use one thing, thanks for trying,” Sean called and was like, ”I’ve already put two pieces in, if you can give me like five or six more, it could be the interior voice of the character.” I said, ”Let’s do it.”

Did you write from inside Chris’ head, or were the landscapes more your inspiration?

After I saw it initially, Sean sent me different parts, the silent versions. So I think I wrote to whatever that little thing required. There were a lot of boundaries, compared to writing an album with the band, which could be about anything. Like, ”It is one minute 30 seconds long, and you want the lyrics to drop out here so the talking can go over it.” All these boundaries were absolutely welcome, ’cause it made it real easy.

As a parent, it’s gotta be hard to see Into the Wild — watching this kid turn his back on his family.

I think parents will learn a lot from this. I think even if they haven’t done anything wrong…yet…it’s gonna have a profound effect. It’s hard to get through a kid’s life without f—ing them up. And no matter how good you are, at some point your kids are gonna have to create their own independence and think that Mom and Dad aren’t cool, just to establish themselves. That’s what adolescence is about. They’re gonna go through that no matter what. And I think that’ll be an interesting time. I’m thinking about it myself. [Chuckles] These are troubled times, too. Do you force your kids to pay attention to what’s going on, or do you let them live their lives outside of it? My hope is that my child is a strong activist. That would make me most proud.

What if she rebels against your liberal politics and becomes a neo-con?

[Laughs] Aaaah… I don’t think so. I really don’t. Just knowing her now? It would be shocking. It’s certainly not in her nature now. She’s 3 years old — that’s like the height of liberalism. Liberalism comes naturally.

You just created this wonderful segue into Body of War, the other film to which you’ve contributed music, because Tomas Young’s relationship with his mom is critical. He couldn’t live without her, almost literally. I understand you met with Tomas and these songs just flowed out of you? Songs are just flowing out of you these days!

They’re all motivated. They have a purpose. I’ve always felt motivated in the band, obviously. Pretty much at all times music motivates me. How can I say this without sounding in any way proud of myself? Obviously I’ve always written songs that are critical of our government, and talk about our times. Hopefully you attempt to be timeless while doing it. Tomas’ story allowed me to write the song that I was always thinking of. I think the other thing with all these songs is I just kind of got out of the way. I didn’t say, Well, it needs to sound more like this. Maybe because they weren’t ”band” songs, I wasn’t thinking they had to sound like the band. I just played what I felt and got out of the way.

And how did you get hooked up with Phil Donahue? That’s not an obvious relationship.

Phil and I were part of Ralph Nader’s support group in 2000. And then I just bumped into him and he said, ”I need you to watch this film.” After that it was real easy.

Were there things this movie brought to your attention that you hadn’t understood before?

Plenty of stories have been told — and not enough people have heard them — about what’s been criminal about this war. You have the violence, which is downplayed. And the misinformation — why are we there, and can we afford to be there, and where is all this money going? There’s the political side to it, there’s the monetary side, it’s all intertwined. But this is the human side of it. It’s incredibly violent to me just watching what Tomas has to go through on a daily basis to survive. To wake up and have a cup of coffee. Just to live every day, because he signed up on September 13th, and went over to fight the good fight in Afghanistan. He ends up in Iraq. He thinks he’s fighting the bad guys; now he doesn’t know. He’s questioning why he’s even there, and then he’s paralyzed almost upon arrival. And now he has this incredible challenge. And I’ll tell ya, with a lot of friends you always say, ”Well, if you can get through this it’ll get better.” Or ”I helped you make it better. I got this guy on it, we’ll help you out.” For Tomas, it’s not getting better. In fact, it’s just getting worse. Phil and Ellen’s movie is incredibly violent, without showing any kind of blood, or guns, or bombs. Just what the remnants are. And that’s as powerful as anything I’ve ever seen. Just one person. Just one soldier. One casualty, of which I think now we have over 25,000. And then they don’t get the proper care. When he came to visit in Seattle, Tomas’ wheelchair didn’t have any brakes. It was a piece of s— that the government had given him. I watch on the news about how these are great men and patriots fighting for freedom, but then the real story comes out about Walter Reid. The real truth is they’re giving ’em jacks—, and there’s like billions and billions of dollars that are unaccounted for that have all gone into the hands of wealthy businessmen that are all somehow connected to the administration. The ineptitude is frightening.

So…what are your plans for election season? What are you focused on?

Um, I’m gonna vote. [Laughs] I’d like people to be educated on the voting machines, making sure that our democracy isn’t being hijacked by computer technology. There’s no reason there can’t be a paper trail on those machines. We had Diebold machines when I worked at a gas station in 1989, so big trucking companies could keep track of the gas they used. I know those machines really well. And there’s no reason why they can’t have a paper trail. And then you have the owner of the company saying in public he’ll do whatever he can to deliver the vote to Republicans — people need to be educated on that.

Will there be a Vote for Change-type activity this time around?

Maybe we’ll just play Ohio. For a month. Ohio and Florida.

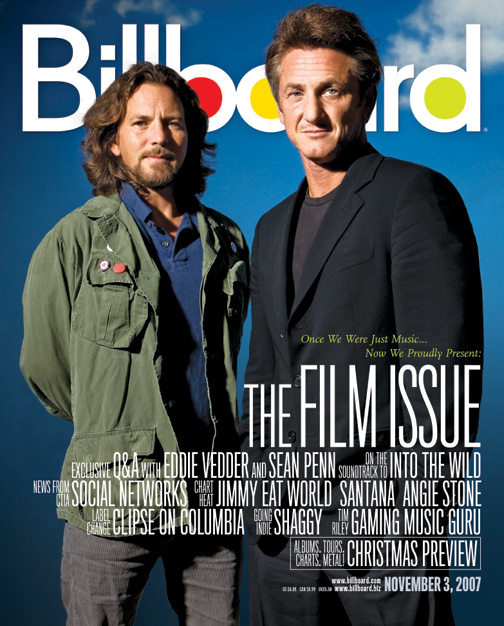

Nature Boys

Sean Penn and Eddie Vedder talk about age, rage and their new film

Time | September 13, 2007

By Lev Grossman

They’re both rich and famous, they’re both notoriously earnest and left-leaning, they both have reputations for being emotionally tortured. So it makes a kind of cosmic sense that Sean Penn and Pearl Jam front man Eddie Vedder would be friends; they have been since 1995, when Vedder wrote music for Dead Man Walking, in which Penn starred. Both are currently experiencing second acts, Penn as a director and Vedder as a film composer. The duo have now collaborated: Vedder has written the sound track for Penn’s movie Into the Wild, based on the book by Jon Krakauer. Later this month Vedder will release a CD of songs written for or inspired by the movie, the closest thing to a solo album he’s ever done.

Into the Wild is the true story of Chris McCandless, a good kid from a prosperous but unhappy family, who left home, burned his money, changed his name to Alexander Supertramp and in 1992 walked off into the Alaskan wilderness. He died there of starvation 16 weeks after he arrived. What was he looking for? Penn and Vedder–who are a lot funnier than they get credit for–talked to TIME’S LEV GROSSMAN about this and other profound questions, like how you keep a huge grizzly bear happy on a movie set.

TIME: What made you pick up Krakauer’s book?

PENN: The cover grabbed me–the bus, the image of the bus with the title Into the Wild on it. I’ve made a lot of decisions in my life that you could call judging a book by its cover. And I’ve become a real advocate of it. So I took the book home, and I read it cover to cover twice, and I went to sleep in the wee hours and immediately got up in the morning, and I saw in essence the movie that you saw last night.

What was it about what McCandless did that got to you?

PENN: I really think that we shouldn’t just accept rites-of-passage opportunities as they come, because what we’ll find is that they don’t come in our world anymore. And we shouldn’t look at them as a kind of luxury or romantic dream but as something vital to being alive. McCandless quotes somebody else in the movie: “If just once you put yourself in the most ancient of circumstances …” This is where nature comes into it–and I think that Eddie and I share this feeling–that every sober-minded person of any belief would probably agree that the biggest issue is quality of life. You’ve gotta feel your own life to have a quality of life, and our own inauthenticity, our corruptions, get in the way of that. The wilderness is relentlessly authentic.

Have you ever gone through anything like that? A rite of passage?

PENN: Formatively the experience I had, where I found the beginning of the map to figure out how to feel my own life, would have come from surfing as a kid. My wilderness is the ocean, and my experience with risk and conquering fear was the ocean.

Being alone like that can help people find themselves, but it can also make them fall apart.

VEDDER: See, I love it. I need it. I’m a better person because of it. I mean, I feel really blessed even to have had the opportunity of disappearing on an island or something and not seeing anybody for weeks. It makes me somebody that somebody else could live with. That’s another thing, when you talk about the environment and how precious it is: it makes us better people.

How did you get into doing soundtracks, what with being a huge rock star and all? Is it a lot different from doing Pearl Jam?

VEDDER: Yeah, it’s easy. Really. I almost don’t remember a thing. It was like I kinda went into some weird space for a week or two, and then I woke up out of this daze, and it was done. I don’t really remember it.

That doesn’t even sound like work.

VEDDER: I was thinking about it yesterday. I don’t trust art that was made easy. If there’s not some kind of pain involved, then I don’t trust it. And I thought, Well, how can I be honest and tell people that it was easy? But what I figured out is that the hard part was 25 years ago, when I went through what this kid went through. I went through pain, but it was just a long time ago. And I guess what’s a little bit worrisome to me is how easy it was to access it. You know? That I just had to barely put my finger in. It was right there on the surface. I thought I’d grown up much more. I’m glad there was a use for it, but now I’ve got to tuck it away again.

So how does it work? Sean, do you just go to Eddie and say, “Here’s a bit with a guy hitchhiking. Write a song that would sound good with that”?

PENN: Well, I’d written the script originally structured for songs. I love that kind of thing in movies. I was born in 1960, so you can do the math and figure out that I was just coming into my own with Harold and Maude, and earlier than that, Simon and Garfunkel and The Graduate, and Coming Home. It just added something, letting your songwriter be a co-author of the script in many ways.

VEDDER: It was like a factory, where I would sit in a chair and they’d hand me instruments. We’d just keep going, and I didn’t have to teach anybody the part or talk them into the idea, the theory, the soul of whatever the piece was. I’d just sit in the chair, and they’d hand me a fretless bass, and they’d hand me a mandolin, and they’d take a second to do the rough mix, and then I’d write the vocal, and it was just quick. It was as in the moment as you could be, and in that way it’s like a great feeling of being alive. You’d hear two pieces at the end of the day–or three–and feel like you were actually doing something on this planet while you were here.

Some of the vocals were wordless, just these howling chants …

VEDDER: That was all stuff I did not-to-picture. In a way–like the music for the scene on the mountaintop–I don’t think I would have done that [if I had seen the footage]. I would have felt too–like if you could be both vulnerable and pretentious at the same time?

PENN: [Laughs.] Leave that to me!

Emile Hirsch [who plays McCandless] goes through a truly shocking physical transformation to show McCandless starving to death. How’d you achieve that?

PENN: Turns out he has phenomenal willpower. A 21-year-old kid, who just got the right to go drinking with the guys in the bar, and he is by choice sober. By choice a monk for eight months. He was in a room watching his feet roll under him on a treadmill or doing pushups or eating another glass of water with lemon in it for dinner every night for eight months. You know, that’s really, really hard.

He has a scene with a bear that got some audible gasps.

PENN: He was an 8-ft. 6-in. grizzly bear, and if he wasn’t a good bear, I wouldn’t be here right now. But no flinching from Emile–he just stood there, six inches away from that thing.

What do you do when the bear’s not being a good bear?

PENN: You say, “Good boy,” all day long. Or the trainer does. And he gives him a lot of chocolate whipped cream.

McCandless doesn’t come off as a saint in the movie. I mean, he won’t call his parents even though they’re desperate to hear from him. He’s angry.

PENN: You know, this is subject to a lot of personal stuff on anybody’s part–yours, mine. My answer to “He should have called his parents” is “Who says?” I understand it, but I walked in my shoes, not his shoes. What I do know is that if you’re not feeling your life, you are obligated first to do everything it takes to feel your life. I’ve done many things without the intention of hurting people that have hurt people. And I’m saying this knowing that I’ve got two kids that are coming up to that age myself right now.

Eddie, you talked before about how much you have in common with McCandless. [Vedder has a famously difficult relationship with his stepfather, as McCandless did with his father.] Did doing the movie help you get over that pain at all?

VEDDER: Not enough. But it’ll do for now. I don’t think it’s gonna go away. I think in the last 10 to 15 years, I’ve just been able to not let that person and that part of me be in charge–that guy is in the car, but we just don’t let him drive. That’s something Springsteen told me once, and it really works. He’ll be talking in your ear in the backseat, but just don’t let him get behind the wheel. And you can be proud of it. I’ve talked to the people that raised me, and I’ve thanked them for giving me a lifetime’s worth of material. I was talking to Bono in Australia last year, and we mentioned something about family histories, and he was like, Wow, they really gave you some good stuff to write about. It was like he wanted to hug them and thank them.

PENN: My mother was reading this article about me in Esquire last month, and she called me up, and she said [Penn does his mother’s voice], “Well, I thought it was an interesting article, but you know, the one thing, every time I’m sitting with you, you have a Diet Coke. Why is it that you’re an alcoholic? I’m the alcoholic!” It was as though I’d stolen her mantle!

The thing I can’t figure out about Into the Wild is if it’s a happy story or a sad one. McCandless experiences so much joy, but then he dies in the end …

PENN: Let me tell you what I think. My Uncle Bill, who was dying–with 13 cousins that he had all with my Aunt Joan, they had a great, happy marriage for all their years. So there he is on his deathbed. He’d been in a coma a couple of days, and a priest has come in to give last rites. This was the first time, Irish that they are, that my aunt let a tear fall, trusting that his coma would make him unaware of it. Well, open come the eyes, and he sees. He catches her–she can’t get away with it. And his last words were “What’re ya crying about? You’re gonna die too.” Chris McCandless lived too short, that’s true, but he, in my view, put an entire life from birth to the wisdom of age into those years.